Meet Gilda Gonzales

Gilda Gonzales, the CEO of Planned Parenthood, is a force to be reckoned with on a mission to provide all people with fundamental human rights: access to equitable and high-quality health care, and the freedom to make decisions about their bodies and lives, no matter what.

It was my honor to get to talk to her about what’s coming up this winter and how we can all do our part to support her and Planned Parenthood Northern California (PPNorCal) in these efforts.

Gilda Gonzales at the 2019 Women's March

HA: What was little Gilda like? Where’d you grow up and what was your family life like?

GG: As early as I can remember, I had a fierce and burning desire to be free, to be exactly what I wanted to be, despite any of the cultural, religious, or family traditions that were strongly recommended.

HA: ‘Recommended’, I love it. And what were those recommendations? Did you grow up in a Catholic household?

GG: Yes, a very, very, very Catholic household. My parents were born in Texas and were extremely poor. Both of them worked in the fields, whether it was picking cotton or vegetables or fruits, really from the time they were around nine or ten years old. And they moved around wherever they could find work with their families. Neither one of them had a high school diploma until they did their GED while in their 40s. My dad was drafted into the military in the early 1950s. And he told me a story recently, that he was supposed to go into the Army. He’d quit his job ready to enlist, but the Army recruiter wasn’t telling him when or where to show up. So, he took it upon himself to go to the Air Force and volunteered where he eventually got enlisted.

HA: He must have been really young at this time, no?

GG: He was in his late teens and while in the Air Force, he acquired the skill of a sheet metal worker. A few years later, he met my mother. She was 19 and he was 24 when they got married.

HA: Did they grow up in the same area?

GG: No, they were in different towns. My mother was born and raised in Presidio, Texas. And my dad was born and raised in Natalia, which is outside of San Antonio. What shaped their life experience and how they raised us was not just the abject poverty, but the racism they experienced in Texas, being treated like second class citizens in a country into which they’d been born. Both of my mother’s parents were born in Texas as well, and my father’s dad was born here and his mother, my grandmother, migrated from Monterrey, Mexico. And because they learned Spanish first in the home before learning English, they had an accent. And the experience of being ‘othered’ because of language, skin color, and other factors, made them make different decisions for their children. So unfortunately, to ensure their children didn’t have an accent and endure their same pain, my siblings and I learned English first, and whatever degree of Spanish that we know now has been a result of us putting ourselves through Spanish classes. I still struggle with my Spanish and continue to be uncomfortable giving public presentations in it.

HA: I’m so sorry your family experienced such institutionalized and cultural racism through which your family’s language and culture were crushed out to a point.

GG: It really informed so much of how my mom viewed education and how we presented ourselves as a family. She was a huge proponent of education, even though she, in fact, did not have her own high school diploma until she was in her 40s. She would always say that “once you have education, they can never take that away from you”. She always held herself with a great deal of dignity and had this way about it that transcended her “status”. She was very particular about all of us presenting ourselves well outside of our home. There was a tension there because this stemmed from a feeling of always needing to watch your own back, and a feeling of being judged. I always had an internal sense of this, basically living in two realities, the one at home and around family and then switching to another mode for the outside world. We were a family of seven with a very large extended Mexican American family. I have 60 first cousins, between my mom and my dad's side, with my Gonzales family primarily in California and my mother’s Dominguez family in New Mexico. I spent my childhood weekends attending local family celebrations of weddings, birthdays, holidays, or just gatherings for no reason and family vacations were spent visiting the other side of the family in the Southwest. The contrast in my realities was amplified by the fact that the working-class neighborhood we lived in and the elementary school I attended were predominantly white. It was like living in a kind of two-prism reality.

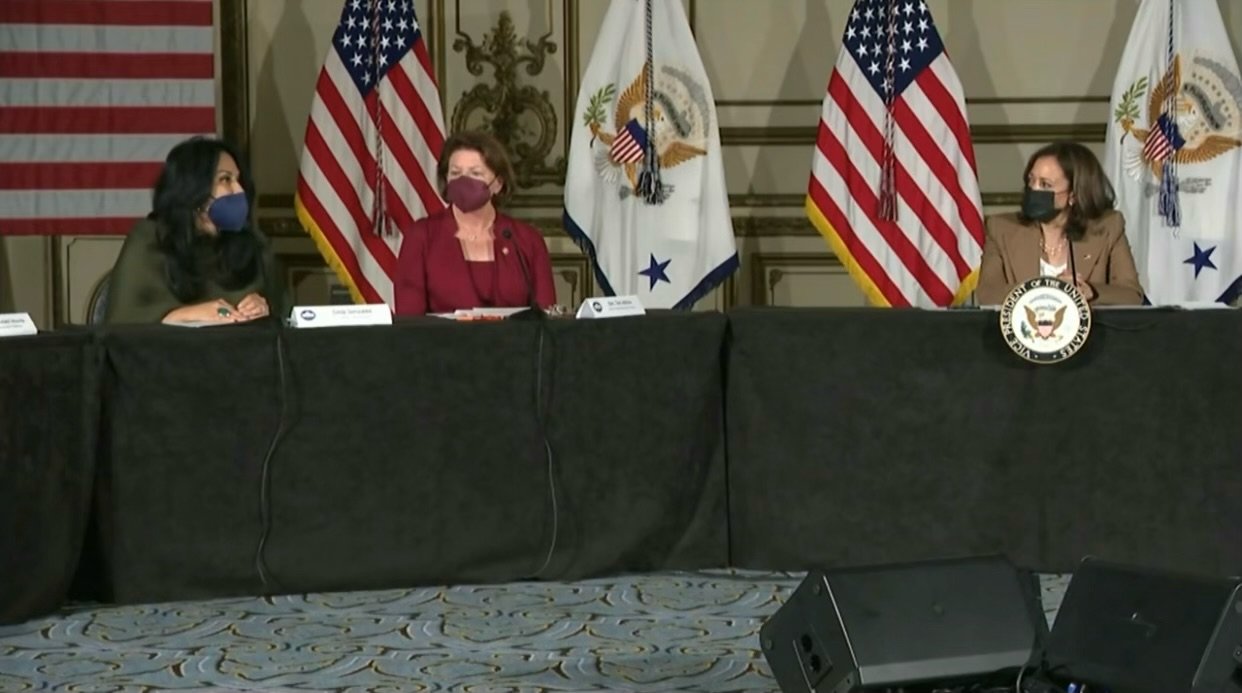

Gilda Gonzales with Vice President Kamala Harris and Senator Toni Atkins at a Roundtable Discussion on Reproductive Healthcare

HA: Yes, I can imagine that. Where did you consider your childhood home base?

GG: California. I was born in Roswell, New Mexico. But when I was less than a year old, we moved to Atwater, a small town in California’s Central Valley because there was an Air Force Base, and my dad was transferred there.

HA: I get that. I moved here at age 6 and still feel like a Californian. When did your interest in activism and human rights really start to feel apparent?

GG: I don’t know why exactly, but from a very early age, I knew I was smart. I read a lot and had a strong sense of my academic ability. I also participated in team sports. I think I was a leader from before I understood what that meant. I also was a feminist before I even knew what a feminist was. The trend lines of my questioning the status quo and wanting to change things were already forming. I remember, when I was very young, my mother used to sign her name in the 1970s as Mrs. Genovevo Gonzales, my dad’s name. And I would ask her why she signed her name that way because her name was Delia Gonzales. And I remember her looking at me - and I was so young and small that she had to look physically down at me to ask, Gilda, where do you get these ideas?”

I had - and still have - no answer for that. I also remember asking my mother as I got older, what did she want to do with her life and what were her dreams? And she would summarily answer: “All I wanted to be is a mother.”. My mother embodied unconditional love and always made us feel loved and adored - even when we disappointed her, so her only dream of being a mother was definitely her truth. I understood what it was to be a mother by experiencing her mothering. And I also understood that I had different dreams and different ideas about who and what I wanted to be. I always gravitated toward social justice leaders throughout my life. Martin Luther King, Cesar Chavez, Gloria Steinem, Dolores Huerta, these people who I could see on TV. They were the people that I wanted to hear from and know more about. These trend lines for who you are begin so young. I ran for class president as early as 7th grade, and it went from there. I just kept showing up and questioning societal barriers and limitations.

“I always gravitated toward social justice leaders throughout my life. Martin Luther King, Cesar Chavez, Gloria Steinem, Dolores Huerta, these people who I could see on TV. They were the people that I wanted to hear from and know more about. These trend lines for who you are begin so young.”

I did have a teacher who was a pivotal role model for me, my first mentor. I took her class, my junior year of High School, Dr. Angie Parga. She was the first educated and professional level Latina I had ever met and has since passed. We used to spend time after class talking and she would take the time to hear me, knowing how to help me see outside of any perceived limits, asking things like, “Gilda, what do you want to be?” I’d already planned since grade school that I was going to go to college. I remember vividly telling my mom to start saving money as early as fifth grade, because I was going to college. And she did; she and I started a modest joint account. So, by the time I was in high school, and Angie Parga started talking to me about who and what I wanted to be, I knew that college was going to be part of the plan, but I hadn’t dreamed big enough until I spoke to her and received that encouragement. She really seeded that notion in me of dreaming big.

I told her that I wanted to be a social worker, and so she’d say, well if you’re going to be a social worker, maybe you should be a psychologist. And if you want to be a teacher, why not be the principal? She also introduced me to my first conferences led by Chicano students, and my first hands-on experience of student activism.

When I was ready to apply for college, Dr. Parga helped me navigate applications for admission and scholarships. I had a plan “A” and a plan “B”. My first option was to get to the Bay Area for undergrad. And to make my mom feel ok about her ‘baby’ moving away, I chose the Catholic option of Saint Mary's College in Moraga. Getting into college felt like my whole world had opened with unlimited possibilities. When I arrived at St. Mary’s, it was a culture shock. Immediately, I realized I’d landed in a very wealthy white student body community. I had never seen so many BMWs in my life. I quickly connected with other Latino students, mostly from similar modest backgrounds, and clung to this small group for support. They were my refuge on a campus that felt like I'd landed on a different planet. During the first years of my college experience, several of my friends became pregnant and then were summoned home. I knew I could not let that happen to me. A college degree was my way forward, my ticket to the life I wanted.

Through some whispers on campus, I learned about the Planned Parenthood health center in Concord. It was a way for me to safely, without judgment or insurance, secure information, birth control and care. Planned Parenthood helped me secure my future - and so it’s not a coincidence that life has come full circle, and 30+ years later, I’m the CEO leading the very same Planned Parenthood that empowered me. Planned Parenthood gave me the care that allowed me to complete the trajectory of my academic and professional goals, and to not let anything get in my way. They allowed me to control my fertility and gave me the ability to fully express myself, creating a situation where I felt my dreams of social change leadership were possible.

HA: It’s amazing how fitting it is for you to now use your education and activism to uplift and protect people who might find themselves in your same shoes. What’s an obstacle you face concerning public perception in doing the work you do?

GG: You're complex. I'm complex. People are not stereotypes. Decisions we make about our health and lives goes beyond any political or social labels. We each have different factors at play at different times of our lives. What’s necessary for basic human rights to be realized is that all people have access to all forms of health care. With the overturning of Roe, there are now 17 states where people have less freedom without access to abortion care.

HA: Wow. So tell me more about that nitty gritty of services and logistics. Can anyone, of any gender come for reproductive health care without insurance?

GG: Yes, we are fortunate here in California to have a state that advances Reproductive Freedom through supportive programs set up so patients can access Planned Parenthood and other community clinics, based on their economic situation, and could in some cases, get free services. About 85% of our patients come to us with some form of subsidized health care, as in, state-provided health care. These are patients who have low incomes and qualify for different state health care programs.

“Decisions we make about our health and lives goes beyond any political or social labels. We each have different factors at play at different times of our lives. What’s necessary for basic human rights to be realized is that all people have access to all forms of health care.”

HA: And Planned Parenthood is picking up the bill on those with low income?

GG: We're getting reimbursed through the state of California and support from our donors also helps cover expenses that may not be reimbursable.

HA: Got it. What would you say is the greatest misconception around Planned Parenthood?

GG: The biggest misconception is that all we do is abortion. And while we're extremely proud of our abortion care, it only represents approximately 5% of our services, depending on the year. So, 95% consists of other health services that are focused on family planning and preventive care. Whether it's birth control, testing and treatment for sexually transmitted infections, preliminary screenings for breast cancer, and hormone therapy for gender transition, the whole host of our services is very robust. And I think that people are mostly shocked by that.

HA: I didn’t realize PPNorCal assisted in Breast Cancer screenings as well.

GG: Yes, we offer breast exams, and we’ll refer patients for mammography as needed. I think that people also have a misconception about who generally comes through our doors.

HA: I feel like I might have personally been the stereotypical assumption: white college student with no health insurance seeking STI or pregnancy tests?

GG: Exactly. That’s the perception. When in reality, 84% of our patients have low incomes (below 200% of the Federal Poverty Level), 75% are Medi-Cal beneficiaries, 46% Latinx, 56% from communities of color, 84% women, 75% between the ages of 18-34, and 12% with primary language diversity.

Another thing people don’t realize is that Planned Parenthood is made up of 50 different entities. That is the biggest misconception that people have. We have a national office that is based in New York. And they do not provide any health care services; they are responsible for national brand and policy. And then there are 49 independently operated and financed Planned Parenthood affiliates serving local communities. It’s really important for supporters to understand this structure, because if they donate to the national headquarters, only a portion of the gift actually reaches us. We need and want people to donate locally. We’d love donors in Northern California to support PPNorCal specifically.

“The biggest misconception is that all we do is abortion. ”

Gilda Gonzales at SF City Hall rally

HH: So how can our readers best support right now?

ACTION STEPS:

Gilda Gonzales is a member of The Club, The Mamahood’s sister organization of women (and gender non-binary) Founders, Owners, Creatives, Leaders. If you have or are creating change through your entrepreneurship or leadership, consider joining.

Apply to join The Club:

Throughout January, 30% of all new Club Membership dues will be donated to PPNorCal.

Join here: www.theclubhouse.io/membership

Curious? Book a call with The Club Founder, Heather Anderson to learn more.